Extras

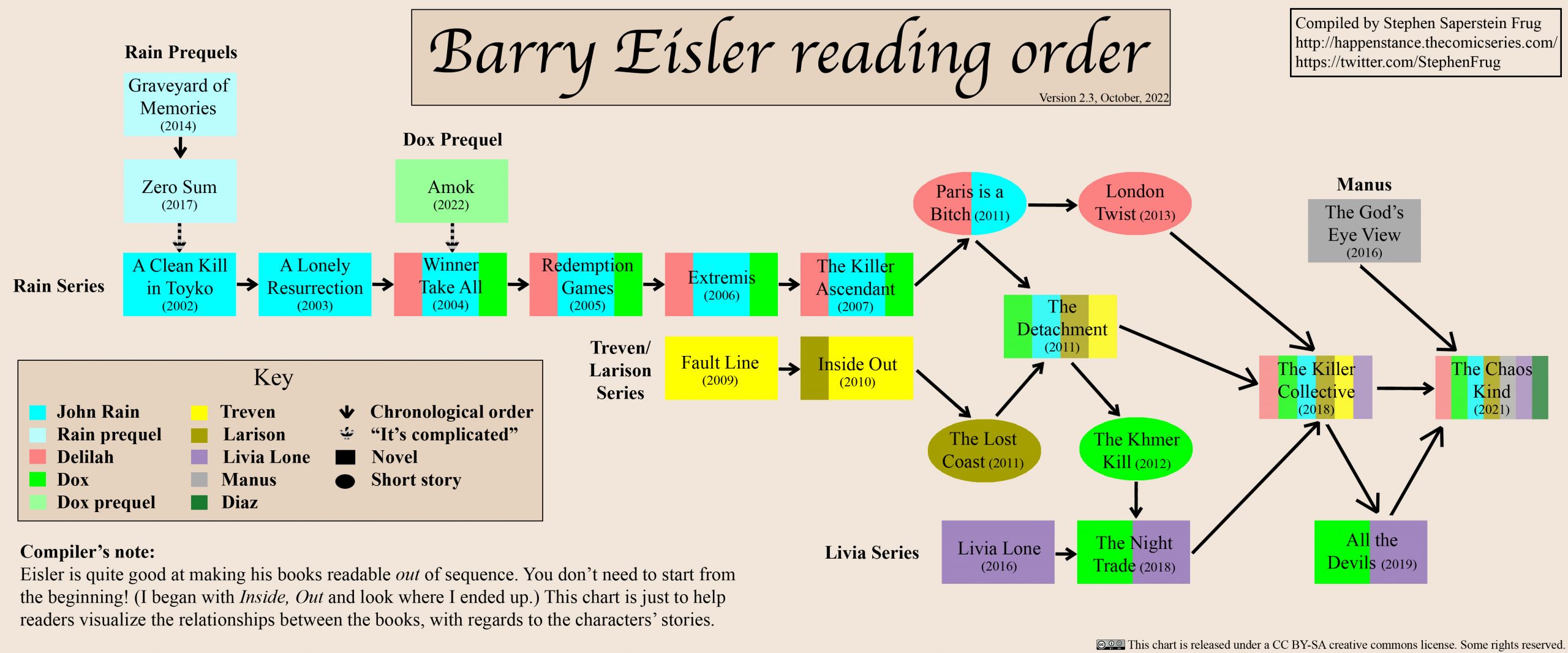

Barry Eisler Reading Order

Book Endnotes

• The Chaos Kind

• All The Devils

• The Killer Collective

• The Night Trade

• Zero Sum

• Livia Lone

• The God’s Eye View

• Graveyard of Memories

• London Twist

• The Khmer Kill

• The Detachment

• Inside Out

• Fault Line

• The Killer Ascendant

• Extremis

• Redemption Games

• Winner Take All

• A Lonely Resurrection

• A Clean Kill in Tokyo

Personal Safety Tips from Assassin John Rain

This article also appears in Crimespree Issue #4

Part of the appeal of my series about the half-American, half-Japanese assassin John Rain seems to be Rain’s realistic tactics. It’s true that Rain, like his author, has a black belt in judo and is a veteran of certain government firearms and other defensive tactics courses, but these have relatively little to do with Rain’s continued longevity. Rather, Rain’s ultimate expertise, and the key to his survival, lies in his ability to think like the opposition.

Okay, get out your notepad, because:

All effective personal protection, all effective security, all true self-defense, is based on the ability and willingness to think like the opposition.

I’m writing this article on my laptop in a crowded coffee shop I like. There are a number of other people around me similarly engaged. I think to myself, If I wanted to steal a laptop, this would be a pretty good place to do it. You come in, order coffee and a muffin, sit, and wait. Eventually, one of these computer users is going to get up and make a quick trip to the bathroom. He’ll be thinking, “Hey, I’ll only be gone for a minute.” He doesn’t know that a minute is all I need to get up and walk out with his $3000 PowerBook. (Note how criminals are adept at thinking like their victims. You need to treat them with the same respect.)

Okay. I’ve determined where the opposition is planning on carrying out his crime (this coffee shop), and I know how he’s going to do it (snatch and dash). I now have options:

- avoid the coffee shop entirely (avoid where the crime will occur);

- secure my laptop to a chair with a twenty dollar Kensington security cable (avoid how the crime will occur—it’s hard to employ bolt cutters unobtrusively in a coffee shop, or to carry away a laptop that has a chair hanging off it); and

- hope to catch the thief in the act, chase him down, engage him with violence.

Of these three options, #2 makes the most sense for me. The first is too costly—I like this coffee shop and get a lot of work done here. The third is also too costly, and too uncertain. Why fight when you can avoid the fight in the first place? This is self-defense we’re talking about, remember, self-protection. Not fighting, not melodrama. As for the second, yes, it’s true these measures won’t render the crime impossible. But what measures ever do? The point is to make the crime difficult enough to carry out that the criminal chooses to pursue his aims elsewhere. Yes, if twenty-seven ninjas have dedicated their lives to stealing your laptop and have managed to track you to the coffee shop, they’ll probably manage to get your laptop while you’re in the bathroom even if you’ve secured it to a chair. But more likely, your opposition will be someone who is as happy stealing your laptop as someone else’s. By making yours the marginally more difficult target, you will encourage him to steal someone else’s.

Which brings us to an unpleasant, but vitally true, parable:

If you and your friend are jogging in the woods, and you get chased by a bear, you don’t have to outrun the bear. You just have to outrun your friend.

Except at the level of very high-value executive protection (presidents, high-profile businesspeople, ambassadors and other dignitaries), you are not trying to outrun the bear. You are trying only to outrun your friend.

Let’s combine these two concepts—thinking like the opposition, outrunning your friend—with an example from the realm of home security. And let’s add an additional critical element: that all good security is layered.

If you wanted to burglarize a house, what would you look for? And what would you avoid?

Generally speaking, your principal objectives are to get cash and property, and to get away (home invasion is a separate subject, but is addressed, like all self-protection, by reference to the same principles). You’d start by looking at lots of houses. Remember, you’re not trying to rob a certain address; you just want to rob a house. Which ones are dark? Which are set back from the road and neighbors? Are there any cars in the driveway? Lights and noise in the house? Signs of an alarm system? A barking dog?

Thinking like a burglar, you are now ready to implement the outer layer of your home security. By some combination of installing motion-sensor lights, keeping bushes trimmed to avoid concealment opportunities, putting up signs advertising an alarm system, having a dog around, keeping a car or cars in the driveway, leaving on appropriate lights and the television, and making sure there are no newspapers in the driveway or mail left on the porch when you’re away, you help the burglar to decide immediately during his casing or surveillance phase that he should rob someone else’s house.

If the burglar isn’t immediately dissuaded by the outer layer, he receives further discouragement at the next layer in. He takes a closer look, and sees that you have deadbolt locks on all the doors, and that your advertisement was not a bluff—the windows are in fact alarmed. If he takes a crack at the doorjamb, he discovers that it’s reinforced. If he tries breaking a window, he realizes the glass is shatter-resistant. Whoops—time to go somewhere else, somewhere easier.

Okay, the guy is stupid. He keeps trying anyway. Now the second layer of security described above, which failed to deter him, works to delay him. It’s taking him a long time to get in. He’s making noise. At some point, the time and noise might combine to persuade him to abort (back to deterrence). But if he insists on plunging ahead, the noise has alerted you, and you have bought yourself time to implement further inner layers of security: accessing a firearm; calling the police; retreating to a safe room; most of all, preparing yourself mentally and emotionally for danger and possible violence.

Now another example, relating to personal protection from an overseas kidnapping attempt. Like everything else, this form of protection starts with you thinking like the bad guy. Your objective is to kidnap a foreigner. Not a particular foreigner (high-value targets are a separate problem, although again subject to the same principles), just any old foreigner. So what do you need to do to carry out your plan?

First, you need to pick a target. This part is easy—any foreigner will do. Next, you need to assess the foreigner’s vulnerability. Where will you be able to grab him, and when? To answer these questions, you need to follow the target around. If he’s punctual, a creature of habit, if he likes to travel the same routes to and from work at the same times every day, you will start to feel encouraged.

But what if instead, during the assessment stage, you see the target go out to his car and carefully check it for improvised explosive devices. Your immediate thought will be: Hard target. Security-conscious. Too difficult—kidnap someone else.

If you’re the potential target, do you see how your display of security consciousness becomes the outermost layer of your security?

But suppose the would-be kidnapper wants to assess a bit further. Now he learns that you never travel the same route to and from work. You never come and go at the same times. He can’t get a fix on your where and when. How is he going to plan a kidnapping now?

Note that, by putting yourself in the opposition’s shoes, you have identified a behavior pattern in which he must engage before carrying out his crime: surveillance. Before you are kidnapped, you will be assessed. Assessment entails surveillance. Now you know what pre-incident behavior to look for. If you were trying to follow you, how would you go about it? That’s what to look for.

Perhaps the would-be kidnapper will discover choke points—a certain bridge, for example—that you have to cross every day on your way to the office. This would be a good place for him to lay an ambush. But because you know this too, you will be unusually alert as you approach potential choke points. As he watches your choke point behavior, he realizes again that you are security-conscious, and thus a poor choice for a target. Again, deterrence. If he is rash and acts at this point anyway, the inner layers of your security—locked and armored vehicle; defensive driving tactics; presence of a bodyguard; access to a firearm; again, most of all, preparing yourself mentally and emotionally for danger and possible violence—all have time to come into play.

Other examples: if you needed fast cash, where would you look to rob someone? Maybe on the potential victim’s way from an ATM? If so, what kind of ATM would you pick? Where would you wait? What if you wanted to steal a car? Assuming you’re not a pro who can pick locks and hot-wire ignitions, where would you go? Maybe outside a video store, or a dry cleaner’s, a place where people leave the keys in the ignition because they’ll “only be gone for a minute”? Now, armed with a better understanding of the criminal’s goals and tactics, how should you behave to better protect yourself?

One common element you might see in all of this is the vital need for alertness, for situational awareness. Understanding where threats are likely to come from and how they are likely to materialize will help you properly tune your alertness. If you are not properly alert to a threat, you almost certainly will be unable to defend yourself against it when it materializes.

Notice that so far the discussion has included no mention of martial arts. This is because martial arts, self-defense, fighting, and combat, while related subjects, are not identical. The relationship and differences among these areas is outside the scope of this article; for more information, check the suggestions for further reading below, especially nononsenseselfdefense.com. For now, suffice it to say that martial arts can be thought of as an inner layer of self-defense. If you have to use your martial arts moves, then almost certainly some outer layer of your security has been breached and you are in a worse position than you would have been had the outer layers held fast.

To put it another way:

Thinking like the opposition; taking threats seriously and not being in denial about their existence; and maintaining proper situational awareness, are infinitely more cost effective for self-defense than is training in martial arts.

Note that I have been doing martial arts of one kind or another since I was a teenager. I love the martial arts for many reasons. I do not dispute and am not discussing their value, but rather am emphasizing their cost-effectiveness in achieving a given objective—here, effective personal protection. No matter what her martial arts skills, the person who recognizes in advance and can therefore steer clear of an ambush has a much better chance of surviving it than does the person who wanders into the ambush and then has to fight her way out.

So practice thinking like the opposition, and you’ll have a better chance of lasting as long as John Rain.

I am indebted for much of what appears in this article particularly to the wisdom and experience of Marc MacYoung and nononsenseselfdefense.com. There is much more to this subject; this article is only a start. To learn more, I suggest:

Gavin de Becker, The Gift of Fear

Marc MacYoung, Cheap Shots, Ambushes, and Other Lessons

Peyton Quinn, A Bouncer’s Guide to Barroom Brawling

If you’re interested in going deeper into the mechanics and psychology of violence, then:

Tony Blauer’s tapes and courses

Alain Burrese, Hard-Won Wisdom from the School of Hard Knocks

Loren Christensen’s books and videos

Marc MacYoung’s books and videos

Peyton Quinn, Real Fighting

If you want to go beyond self-defense and into the realm of combat and killing, then:

Dave Grossman, On Killing and On Combat

Practical Martial Arts Tips from Assassin John Rain

This article also appears in Crimespree Issue #9

Not long ago I shared some thoughts on self-defense in an article called “Personal Safety Tips from Assassin John Rain.” I noted that all good defenses are layered, and that the place of martial arts like karate, judo, etc. is at the inner layer while the place of awareness and thinking like the opposition is at the outer. I made an analogy to firearms in the home: like your punches and kicks on the street, your firearm is your last line of defense against an intruder in your house; your perimeter lights and other means of deterrence, and quality locks and other means of delay, are your outer layers. I think this analogy makes the relative cost effectiveness of the inner and outer layers of a defense system pretty clear. After all, assuming you’re not living out some Rambo* fantasy, would you rather shoot it out with an intruder in your bedroom or just have him take one look at your house and decide to rob someone else?

But no matter how much I talk about awareness and avoidance, people always want to hear about martial arts, too. It seems the Paralyzing Nerve Point Strikes of Long Dong Do are sexier than just knowing where trouble is likely to occur and arranging to not be there when it does. All right, let’s talk a little about the “sexy” stuff. But please, let’s keep in mind what really matters—awareness and avoidance.

That last sentence is worth a pause. If you think situational awareness has nothing to do with self-defense (hint: it has everything to do with it), you’d be at the bottom of the food chain in John Rain’s line of work. The survivors—and yes, after a quarter century in the business and combat all over the world before that, Rain is one of them—don’t spend a lot of time on fantasy scenarios because they know that, except in the movies, they’re not going to be attacked by ninjas. They focus on what’s likely to happen and spend their time preparing for that. If you want to survive, you should do what the survivors do.

Survivors work backwards. They reverse engineer the problem. They ask, “What kind of attack am I likely to face?” And they design their training and defenses, including martial arts, accordingly.

How about you? What kind of attack are you afraid of? A mugging? Someone drunk and belligerent in a movie theater or at a concert? A fanatical football fan? If you’re a woman, you’re most likely concerned about rape; I’ll come back to that in a moment.

Let’s go with these for a minute. Imagine them. Do you see your attacker adopting a “put ’em up” stance before launching? Executing a spinning back kick? A “fingers of death” thrust to one of your nerve centers? In the real world, people don’t attack like that. They’ll lower their head and charge like a bull. Or try to grab you in a bear hug or headlock. Or throw a John Wayne roundhouse. These are your most common street attacks. But how many martial arts dojos devote significant time to learning how to counter these attacks? Versus how many devote significant time to learning how to counter pretty roundhouse kicks to the head?

The title of this piece is “Practical Martial Arts,” right? Practical as in, “concerned with actual facts and experience, not theory.” People who don’t train for the attacks that really occur are learning ingenious solutions to fantasy problems**. They’re getting really, really good—at the wrong thing***. They’re the people Rain cuts through like a buzz saw if they get between him and a target.

What about training? Again, work backwards. Whatever you think you’re likely to face, you should try to get your training to imitate is as closely as possible. The more realistic your training, the better prepared you’ll be for the real event. This is obvious, right? Would you trust a surgeon who had only read an anatomy book? Or would you prefer someone who’d worked on cadavers and animals? In fact, wouldn’t you most prefer the surgeon who had actually performed the operation in question hundreds of times? Bruce Lee said, “The best preparation for the event is the event.” This is a profound statement and worth pondering.

A few hints: real violence involves fear and other emotions that will cause your body to dump large helpings of adrenaline into your bloodstream. If you’re not accustomed to it, adrenaline will cut off your access to whatever training you thought you had and cripple your ability to respond effectively. Most dojos give a nod to adrenal stress training by having their students spar. But how much like the real event is point sparring, with light contact and no shots to the head? With rules and a referee and consenting players? With no “woofing” or verbal aggression, no uncertainty about the other person’s intentions beforehand? Introduce yourself to adrenal stress training before the actual event so you’ll be better able to handle the adrenaline dump during the real thing****.

I know what you’re thinking now… hey, he promised to talk about martial arts and there’s nothing in here about karate and kung fu and all that stuff! I mean, who would win between an aikido master and a savate master? Come on, tell me!

I’ve always found these questions strange. After all, are you planning on becoming a judo master? Do you expect to have to fight one? If not, how is the question relevant to you? Pick an art based on how, how often, and how long you’re going to train, and on whom that art will help you defend against, not based on hypothetical death matches between wizened martial arts masters.

Here’s another hint: training matters a lot more than technique. What difference does it make if you’re using a boxer’s punch or a judo throw or a karate kick if you haven’t practiced the technique 10,000 times or more? (sub-hint: techniques that can be drilled more quickly can be learned more quickly, too. Ten thousand repetitions of a drill that takes one minute takes less time than 10,000 reps of a drill that takes five minutes. So simple moves can be learned more quickly, and are less likely to fail under adrenal stress, too).

As for specific arts, I tend to favor the ones that can be practiced “live.” Boxing, judo, jujitsu, muay thai, sambo, and wrestling are all examples of arts that, by their nature, can be practiced as a sport against a determined opponent. If you’re trying to learn how to weave off the line of an incoming punch, it helps if the punch is thrown by someone who’s really trying to knock your head off. If you’re trying to learn how to hit someone with a hip throw, it helps to learn how to do it against an opponent who’s trying his hardest to stop you. Yes, I know neither of these examples is the same as the “real thing.” Training is an approximation. The closer the approximation, though, the better the training.

A few paragraphs up I promised to mention women and defense against rape. Let’s work backward again, as we know survivors do. What does a rapist need to do to carry out a rape? He needs to be very close to you, right? That’s grappling distance. So other things being equal, which is a more practical martial art for fighting off a rapist: a grappling art like Brazilian jiu-jitsu (BJJ), or a kicking art like Tae Kwon Do (TKD)? And which kind of training will give you better adrenal stress inoculation against a rapist’s attack: rolling on the ground face to face with a partner who’s trying to pin you, armbar you, strangle you, and otherwise submit you using all his strength, or point sparring with a partner who’s trying to kick you? Which art is a better approximation of what you’re training for? *****

If you’ve never been grabbed violently and thrown into the wall or onto the ground, the emotional shock of the experience is apt to be as debilitating as the physical event. The whole feeling will be completely unfamiliar to you; the chances of your freezing are high. But a woman who trains in a grappling art like judo or BJJ gets thrown around every day. She’s used to it—she has been partially inoculated against the effects of adrenal stress. When the real thing happens, it’s therefore considerably less shocking; the danger of freezing, considerably lower.

A more specific point: a rapist is likely trying to position himself between your legs. A scary thought, true. But one of the strongest positions in BJJ is the “guard,” where you control your opponent in precisely this fashion—by holding his torso between your legs. A rapist trying to force himself between the legs of a properly trained BJJ woman is therefore putting himself in a position the woman has actively sought to put her opponents in thousands of times before, a position from which she has trained and learned options like armbars and strangles and escapes. What does the TKD trained woman do from here? How familiar is the position to her? What sort of “muscle memory” and stress inoculation is she relying on?

Back to martial arts generally. I don’t mean to imply that arts like aikido, hapkido, karate, kung-fu, TKD, etc. aren’t combat effective; I know they can be. But because the way these arts are taught and trained is a more distant approximation of the “real thing” than is, say, a boxing or wrestling match, if you’re talking about a fight, or than, say, BJJ, if you’re talking about an attempted rape, the learning curve is longer. Again, you have to ask yourself how long you’re going to train, and how often, and measure the answers against your objectives.

But remember, none of this matters as much for your safety as awareness and avoidance. No matter what your martial art, make sure you practice those.

Further reading and training:

Awareness and avoidance (there’s a reason this category comes first, by the way):

Gavin DeBecker, The Gift of Fear

Marc MacYoung, Cheap Shots, Ambushes, and Other Lessons

Peyton Quinn, A Bouncer’s Guide to Barroom Brawling

Mechanics and psychology of violence:

Tony Blauer’s tapes and courses

Alain Burrese, Hard Won Wisdom from the School of Hard Knocks

Loren Christensen’s books and videos

Marc MacYoung’s books and videos

Effects of adrenal stress on combat preparedness:

Dave Grossman, on killing and on combat

Peyton Quinn, Real Fighting

Firearms training and justifiable use of lethal force:

Massad Ayoob

* Tip of the hat to David Morrell, writer of the terrific First Blood and creator of Rambo.

** As noted by Peyton Quinn of the Rocky Mountain Combat Applications Training institute. I took his course, and recommend that you do, too, if you’re serious.

*** I borrowed that one from Tony Blauer. Took one of his courses, too—and and recommend that you do, too, if you’re serious.

**** For a focus on adrenal stress in unarmed encounters, Peyton Quinn’s RMCAT is the place to go. For adrenal stress firearms training, Massad Ayoob’s Lethal Force Institute is incredible.

***** I can hear the TKD people already: with TKD, you take the rapist out with punches and kicks before he even grabs you. Well, maybe, but… how did you know he was trying to rape you before he started trying to rape you? By the time you’re sufficiently convinced of his intentions to respond with violence, my bet is that you’ve already been grabbed and it’s now a little late for TKD distance. This is doubly true for date rape.

Surveillance/Countersurveillance

This article will give you some background on surveillance and countersurveillance, but no amount of theory can substitute for the real thing. So if you’re serious about learning how to follow someone undetected and how to detect someone who’s trying to follow you, you need to get out there and practice. Practice means picking a subject and following that person around without his or her seeing you. But be careful: to anyone who notices what you’re up to, your behavior will be indistinguishable from that of criminals, and you can easily get yourself into trouble with this exercise.

The difficulty of surveillance will generally be a function of four things: the environment, the surveillance consciousness of the subject, the resources you can deploy, and your objectives. These variables function together, but for now, let’s examine them one at a time.

Where is the surveillance going to take place? In an empty park at midday, or at a crowded shopping mall on a weekend? Obviously, the former offers you few opportunities to obscure your presence, while the latter offers many: as a rule, the more people are around for foot surveillance, and the more cars for vehicular, the easier it is to stay concealed.

How surveillance conscious is the subject? On one end of the spectrum is someone who is truly clueless: no instinct, no training, no notion that someone might be following him as he ambles along, jabbering into a cell phone or plugged into an MP3 player. You can follow this person almost anywhere without being detected. On the other end of the spectrum is the person with instincts, training, and experience, who expects that she’s being followed and is determined to identify and/or lose her pursuers.

What are your resources? Solo surveillance is hard. A small team is better. A large team is better still. At the height of the Cold War, the Soviets were able to deploy hundreds of agents to watch suspected CIA officers move around Moscow. With that many resources, the Soviets could put in place what’s called “static surveillance”—the equivalent of a zone defense in basketball. As the subject moves, surveillance doesn’t move with him; instead, he just passes from zone to zone. Because static surveillance doesn’t move, it does nothing to reveal itself, and is therefore very hard to detect.

What are your objectives? If you’re a terrorist looking to kidnap or assassinate a foreigner, the purpose of your surveillance is probably only to determine when and where the target is vulnerable. This kind of surveillance is relatively easy, because it can be conducted from a distance no closer than what’s necessary to determine what time the target leaves his house every morning, what car he uses, what route he uses, and whether he’s security-conscious. But if you’re a Chinese domestic operative tailing a suspected CIA officer around Beijing, and you’re trying to catch the officer in the act of a dead drop or other form of clandestine communication, your surveillance needs to be close and constant—a much more difficult operation.

You can see how these variables work together. If your target is surveillance-conscious, you can compensate by having a large, professional team. If the environment is crowded and fluid, you probably can conduct the surveillance alone. And so on.

In any event, when you’re conducting surveillance, you have to avoid marked behavior. Marked means anything that’s not the norm. With regard to personal appearance, excessively long or short hair would be marked. Likewise facial hair. Or visible tattoos. Eyeglasses are ordinary and common enough to be generally safe for surveillance, but an overly stylish pair would be marked.

Some examples of marked clothing are hats, bow ties, and suspenders. Marked cars include anything bright, expensive, stylish, or new. Marked behavior includes an odd gait, like a limp.

The point is, anything that draws attention to itself, anything that is more memorable than necessary, is marked and should be avoided. Pause for a moment and think. What kind of cars do you tend to notice and remember? What kind of clothes? Those are the ones you need to avoid if you’re intent on remaining undetected.

Of course, what’s marked in one setting might not be marked in another. Know your environment and learn to blend into it. The better you know your environment, the better you can adjust your clothing, behavior, and “vibe” so you won’t stand out. And you can use marked behavior as a distraction: start with a baseball cap, for example, and the subject might very well notice it to the exclusion of your other features. Later, when you’ve discarded the cap, you will have effectively disguised yourself.

The same factors by which we measured the difficulty of surveillance (environment, surveillance consciousness of the subject, resources you can deploy, your objectives) apply to countersurveillance, too. The difference lies in the distinct factors countersurveillance controls: while surveillance usually controls the resources it can deploy and its objectives, countersurveillance selects the environment and awareness within that environment. In other words, when conducting countersurveillance, you should manipulate the environment to force surveillance out into the open, and know what to look for so you can spot it.

The goal of countersurveillance is to make surveillance do things that no one else in that environment is doing (again, this is why static surveillance is so hard to beat; you can’t get it to react). But how?

Start by choosing the environment. Unobtrusive countersurveillance is hard if you don’t know the terrain. Spies who want to avoid behavior that could confirm the opposition’s suspicions therefore go to great lengths to plan what are known as surveillance detection routes (SDRs), which are ostensibly normal courses but which in fact make things difficult for a surveillance team.

A good SDR usually combines low cover for a surveillance team with a variety of ingress/egress options for the subject. In a vehicle, this could mean a “shortcut” through neighborhood streets with little covering traffic but with many different outlets. A route like this forces a surveillance team to follow you closely because the team can’t predict which road you’re going to take out of the neighborhood, while the lack of traffic in the neighborhood makes it easier for you to spot the team. On foot, a stroll into a relatively empty park with multiple entrances and exits and perhaps its own subway station has the same effect. Surveillance has to move in close or risk losing the subject at one of the many points of egress, while the lack of pedestrian traffic deprives surveillance of opportunities to conceal its presence.

Objectives matter, too. Do you only want to confirm the presence or absence of surveillance? Do you care whether the people watching you know you’re surveillance-conscious? Do you want to lose surveillance if it’s there? You can think of these three operations as forming a continuum.

Scenario One: Confirm that you’re being followed without the follower recognizing what you’ve done. This is difficult because your countersurveillance moves must all be disguised as ordinary behavior. Stopping suddenly and looking behind you might be effective countersurveillance, but it’s also obvious. Looking behind you for traffic as you turn to cross a street is more subtle, and more difficult.

Scenario Two: If your unobtrusive efforts have failed to flush out surveillance, use provocative techniques—methods that surveillance will have a hard time beating but that will reveal to surveillance, if it’s there, that you are surveillance-conscious. Dramatically changing pace tends to force surveillance to follow suit and reveal itself. Get on several elevators. Get off a train and wait on the platform until it’s clear. Use your imagination: If you were following someone, what would make your job difficult? Do that.

Scenario Three: Decide whether to abort your mission or to evade the surveillance. Aborting requires no further discussion; generally speaking, you just wait until next time. Evasion calls for deception and suddenness.

If you’re trying to spot surveillance, you need to know what kind of interest the opposition has in you. Are you an intelligence agent trying to operate “in the gap”—that is, in the momentary blind spot of enemy surveillance? Are you a foreigner who might be targeted for a kidnapping? An ordinary citizen who’s being sized up for a street crime? Know your enemy and you will learn to recognize him by his behavior.

To put it another way: The secret to good surveillance and countersurveillance, like the secret to effective sales and romance and indeed to life itself, is the ability to put yourself in the other party’s shoes. As you get better at surveillance, you’ll learn what makes surveillance effective and what can make it weak. This understanding will make you better at countersurveillance, too. And as you get better at countersurveillance, you get the picture.

You might be thinking, “This is all a lot of cloak-and-dagger stuff. I’m just a regular person. What does any of this have to do with me?”

Well, you probably won’t find yourself up against something like the old KGB, it’s true. But you might find yourself traveling abroad, perhaps in a place where kidnapping or killing a foreigner like you is worth something. Those operations require surveillance. So do many ordinary street crimes. And the best thing about developing your surveillance consciousness isn’t even that it helps you spot surveillance. The best thing is that someone who’s following and assessing you will see that you’re surveillance-conscious, and decide to kill or kidnap or rob someone easier. Not pretty, but that’s the way it is.

That’s enough reading. Now go practice.

Martial Arts in the Rain Books

This is a very general guide to the martial arts featured most prominently in the Rain books. Purists, remember—this is broad brush! Whole books have been written on these arts; my intention here is to give only the fundamentals necessary for an appreciation of the combat styles that appear in this book.

Aikido: Characterized by joint locks, throws, and a focus on techniques from a standing position. Aikido emphasizes flowing with your attacker’s energy rather than fighting it, hence its name, whose three Japanese characters together mean, “the way of meeting energy.”

Brazilian jiu-jitsu (BJJ): Characterized by an emphasis on ground fighting, and a philosophy of first achieving a dominant position (“establishing your base,” as Rorion Gracie puts it) and then using joint locks and strangles to finish off your opponent. BJJ was derived from traditional Japanese jiu-jitsu by the fecund Gracie clan (see The Gracie Way: An Illustrated History of the Gracie Family, by black belt Kid Peligro) and is now practiced all over the world.

Combatives: Loosely, techniques that are simple to learn and apply, that are intended to be lethal or at least disfiguring, and that are not really part of any formal system. The bronco kick Rain uses to dispatch Flatnose in A Clean Kill in Tokyo is one such technique. For it and others like it, I recommend the classic Get Tough: How to Win in Hand-to-Hand Fighting by W. E. Fairbairn.

Judo: Characterized by throws, joint locks, strangles, and a focus on standing and ground techniques. Judo, whose two Japanese characters together mean “soft way” or “flexible way,” is perhaps misnamed, as anyone who has been on the wrong end of the art can attest. The culture of judo is more competitive than that of aikido; its founder, Jigoro Kano, intended judo to be taught not only as a course of physical education but also practiced as a sport, as indeed it is.

Karate: Characterized by its emphasis on punches and kicks. The two Japanese characters that comprise the word together mean “empty hand.” Karate training consists of sparring and also of kata, or forms, which I once heard aptly described as “the theory of karate”; it’s the latter that gives away the assassin Rain thinks of as “Karate” in the Macau Mandarin Oriental gym in Winner Take All.

Kendo: A modern art and sport derived from traditional Japanese swordsmanship. Like western fencing, kendo is practiced and fought with armor (bogu) and non lethal swords made from bamboo (shinai). Practitioners become adept in a variety of slashes, thrusts, and parries, and their skills can translate into dexterity with sticks, canes, and similar weapons with reach.

Mixed Martial Arts (MMA): Characterized by a focus on transitioning among and fighting at the punching/kicking, takedown, and ground-fighting ranges. Popularized by the Ultimate Fighting Championship, Pride, King of the Cage, and other competitions.

Sambo: Characterized by its emphasis on joint lock submissions, particularly to the legs and ankles, this Russian wrestling style is trained both as a martial art and as a sport. The increasing prevalence (and the need to defend against) leg submission attacks in jiu-jitsu and submission wrestling can be attributed to sambo’s influence.

Savate: Characterized by its precision kicks performed shod, and including punching, grappling, and weapons. Also known as boxe francaise, or French kickboxing, although purists distinguish. Savate is trained both as a martial art and as a sport.

Wrestling: Characterized by its emphasis on takedowns and ground fighting. If you’ve ever seen two kids fighting, you have a decent idea of what (unpracticed) wrestling looks like. There are many varieties, all of which have martial applications and most of which are practiced as sports. Among the better known are Greco-Roman, which focuses on upper-body throws, with no attacks to or defenses with the legs; freestyle, which concentrates on takedowns; “folk-style,” which includes takedowns and ground fighting; sambo, a Russian art that includes joint-lock submissions, particularly to the legs and ankles; and submission fighting, which focuses on joint locks and strangles to submit the opponent.

John Rain vs Jack Reacher

This appeared on Lee Child’s forum a few years ago. Some people were asking who would win in a fight between Rain and Jack Reacher, Lee’s great series character, so I solicited Rain’s thoughts. The resulting conversation isn’t up on Lee’s forum any longer, but it’s fun so I thought I’d repost it here. Enjoy.

Okay, I just checked with Rain. “Could you handle this guy Reacher?” I asked. Here’s how the conversation went:

Rain: “What do you mean, “handle?”

Me: “You know, could you beat him in a fight?”

Rain: “A fight?”

Me: “Yeah, a fight. Mano-a-mano, who would win?”

Rain [after a pause]: “Barry, I’ve been talking to you for years, and… Jesus Christ, haven’t you learned anything?”

Me [embarrassed]: “What do you mean?”

Rain: “First of all, I haven’t been in a ‘fight’ probably since high school. Check with Reacher, and he’ll tell you the same. Fighting is for amateurs.”

Me: “Sure, but…”

Rain: “But what? Why the hell would I want to ‘fight’ Reacher?”

Me: “I mean, if you had to.”

Rain: “Why would I have to?”

Me [struggling to think of something]: “I don’t know… maybe if there were a contract. And you had to take him out, and just when you were about to do it—”

Rain: “Barry, I’m disappointed. I thought you were past this ‘who-would-win-between-a-tai-chi-master-and-a-karate-master’ macho fantasy bullshit.”

Me: “I’m not. That’s partly why I’m a writer.”

Rain: “Well, I’m not a writer, I’m a survivor. And you don’t survive in my business by going head to head with men like Reacher. He’s skilled, he’s experienced, and he’s got a significant size advantage.”

Me: “But if you had to—”

Rain: “All right, just to end the conversation. I wouldn’t even think about taking him out without stealth, surprise, and a tool. Good enough?”

Me: “But if he saw you coming—”

Rain: “I’d run away.”

Me: “Run away?”

Rain: “Yeah. You can translate that as, ‘live to fight another day.'”

Me: “So you’re saying…”

Rain: “I’m saying when two tigers fight, one is wounded and the other dies. Some days it’ll be one of the tigers, some days the other. Either way, both tigers lose. What don’t you understand about that?”

Me: “I don’t know. I guess I hadn’t thought of it that way.”

Rain: “Okay, now you know. When guys like Reacher and me catch sight of each other, we instantly recognize what the other guy is all about and we’re both happy to steer clear. That’s the way it works in the real world. The rest is just a chop-socky movie.”

Me: “But maybe I could come up with some circumstances that would force—”

Rain: “Yeah, yeah, I get it. Look, do me a favor, give Reacher a message from me, okay?”

Me: “Yeah, sure.”

Rain: “Tell him I like his style. But he ought to get laid more often. It’ll loosen him up.”

Me: “I’ll pass that along.”

Rain: “You working on the sixth story?”

Me: “Just finished the outline.”

Rain: “They still think it’s all fiction?”

Me: “They seem to.”

Rain: “Good. I don’t want anyone looking for me. Keep up the good work. But enough of the killer ninja combat questions, okay?”

That was it. Not quite what I was expecting, but with Rain it never is.

Barry Eisler on Andrew Vachss

100 Must-Reads (PDF)

Pioneering and Popularizing the Modern Spy Novel

Read Barry’s Intro to Amazon’s Reissue of all the Bond Books

Barry's Intro to "For Your Eyes Only"

What is it about Bond?

As I wrote those first five words of my introduction to “For Your Eyes Only,” Ian Fleming’s first collection of short stories, I considered referring to the world’s most famous fictional spy by his full name, and then decided it was unnecessary. After all, we all know Bond.

Or do we? Certainly we know the name. But what about the man – his hopes, his fears, his doubts, his origins? What goes on underneath the suave surface of a legend? For that, you have to read the books.

I read them all many years ago, long before I became a writer myself. And in rereading “For Your Eyes Only” to write this introduction, I realized the debt my own character, the half-Japanese, half-American assassin John Rain, owes to the famous spy who came before him. Fleming did it all first, and he did it well.

If you’re looking for what you know, you’re sure to find it in this thrilling collection of stories. Exotic locations like the Seychelles islands in the Indian Ocean, where The Hildebrand Rarity opens with Bond spear-fishing a Stingray; perfectly executed action sequences like the motorcycle assassination that opens From A View to a Kill; gorgeous, dangerous women like the avenging angel of For Your Eyes Only, the title story.

All of which, as the lawyers say, is necessary, but not sufficient. Because the books are more than just locations, action, and Bond’s refreshingly antiquated view of women. They’re also about Bond himself. Ever wonder where and how Bond lost his virginity? From A View to a Kill is the place to find out. Where did he acquire his worldview? In Quantum of Solace, Bond receives an unforgettable lesson on human nature. How does Bond feel after he has killed? In Risico, you’ll find the answer might not be what you think. Does Bond have a soft side? He shows one in The Hildebrand Rarity…

If you don’t know Bond, “For Your Eyes Only” is a great place to start. If you think you know him, this collection will deepen your understanding and your appreciation. Either way, you’re certain to enjoy your time with Ian Fleming’s unforgettable creation. He’s a professional, but not without rough edges; determinedly cynical, but driven by some inner decency; larger than life, and yet surprisingly human. All of which makes James Bond what he is: the best in the business.

Top Ten Tokyo Bars, Coffee shops, Jazz Clubs, and Restaurants

Tokyo has an overwhelming number of incredible bars, coffee shops, jazz clubs, and restaurants, and narrowing them down to the top ten was a difficult, subjective, and somehow unfair task. But here’s my cut. Enjoy these knowing that you can’t go wrong with any, and that there are many, many more places in Tokyo like them. For a more complete yet thoroughly offbeat guide to the city, I recommend Rick Kennedy’s Little Adventures in Tokyo, which introduced me to Tsuta, included below, and to many other little adventures.

1. Old Imperial Bar. Located on the second floor of the Imperial Hotel in Hibiya, the Old Imperial is past its prime but still has an air of history, gravitas, and discretion. And where else can you get a twenty-one-year-old Bruichladdich?

2. These Library Lounge. Wonderfully intimate, eclectic bar in Nishi-Azabu. Soft lighting, thousands of books lining the walls, a table made from a door. Secret alcoves with chatting, quietly laughing parties. Slowly thins out towards four a.m., after which you feel like These (“pronounced “tay-zay”) and Tokyo are a present wrapped exclusively for you.

3. Bo Sono Ni. Modern but classic bar in the basement of the BigMound Building in Nishi-Azabu. A wonderful fireplace; great selection of single malts; quiet laughter and conversation until four a.m.

4. Bar Satoh. It’s in Osaka, not Tokyo, but I love Bar Satoh so much that I moved it to Tokyo in A Clean Kill in Tokyo. Proprietor Satoh-san makes four annual pilgrimages to Scotland, and serves nothing but the exclusive whiskeys he brings back with him (his one concession is Guinness stout, on tap). The music is all jazz and the ambience is low-key, but not leaden; exclusive, but not snobbish; whimsical, but with vision and taste. Bar Satoh was my introduction to unusual scotches like Caol Ila, and to jazz greats like Kurt Elling and Monica Borrfors.

5. Heartman. Old-fashioned, high-end bar in Ginza. Bartenders in white shirts and black bow ties. Small, dark, intimate, comforting; on the second floor and overlooking a nameless street. Outstanding selection of single malts.

6. Tsuta. Hidden jewel of a coffeeshop in Minami-Aoyama. Featuring a serene garden, classical music, and reverential preparations by proprietor Koyama-san.

7. Alfie. Cramped, authentic jazz club in the Roppongi entertainment district. Some friends took me there in 1993 to see pianist Junko Onishi, and that’s where the character Midori Kawamura was born.

8. Body & Soul. Another wonderful jazz club, this one in Minami-Aoyama. Every seat in the house is good. On my first trip, I was close enough to the stage to shake hands with the drummer. Akiko Grace was playing that night, and I was hooked for life.

9. Las Chicas. Eternally hip restaurant in Aoyama with charmingly slow service, great changing menu, and eclectic foreign and Japanese clientele. Got stuck here in a snowstorm in 1994, and will never forget watching Tokyo go magically white over multiple hot cocoas.

10. T. Y. Harbor Brewery. Spacious restaurant and microbrewery with outdoor seating right on the water in resurgent Shinagawa. The food is great, the atmosphere confident but relaxed, and the vibe among patrons is, “Why go to Nishi-Azabu when T. Y. is right here?”

Top Ten Single Malt Scotches

Over the last decade, single-malt whiskey has grown markedly in popularity and price—an understandable trend, given its richness and complexity. Here is a quick primer on the subject, along with a recommendation of John Rain’s Top Ten.

First, some terminology:

- Whiskey (spelled whisky in the UK) is an alcoholic beverage derived from barley.

- Grain whiskey is made from unmalted barley.

- Malt whiskey is made from barley that is first malted—that is, sprouted and dried. The extra steps of sprouting and drying are part of what makes malt whiskey more complex and more expensive than grain whiskey.

- Scotch whiskey is by definition made in Scotland. Malt whiskey produced elsewhere can’t be called Scotch (just as a sparkling wine produced outside Champagne, no matter how fine, can’t be called Champagne).

- Single-malt whiskey is malted whiskey distilled at a single distillery (for example, Cragganmore, more on which below).

- Blended whiskey is a mix of malted and grain whiskeys (for example, Johnnie Walker).

- A single-barrel single-malt, or single single, is a single malt produced from a single barrel. By contrast, a typical single malt is mixed from multiple barrels at a single distillery to achieve a consistent house style. Single singles are the most sought-after, rare, and expensive of all whiskeys. They are often signified with a vintage, such as the 1949 Macallan.

Second, some points on geography. Scotland is generally divided into four main regions: Highlands, Lowlands, islands (chiefly Islay, pronounced eye-luh), and Campbeltown. Each region is known for a certain style, with the Highlands perhaps the most approachable (and most widely known), and the islands, with their strong notes of smoke and sea, taking a bit more getting used to.

To learn more, I recommend Michael Jackson’s Complete Guide to Single Malt Scotch.

And now, in no particular order, a highly subjective Top Ten.

1. Cragganmore. AHighland malt and a great place to begin. Approachable, suitable as a starting point for a second glass of a variety of other whiskeys or, indeed, for another Cragganmore. A good value. Try the twelve-year-old.

2. Macallan. A Highland malt and the exemplar of the big sherried style. Expensive, especially the older bottlings, but worth it. I once had the great privilege of sampling a 1949 single single and a 1954 single single. They were divine. They were also $4000 and $3000 a bottle, respectively! The best value is probably the eighteen-year-old.

3. Highland Park. From Orkney Island, the northernmost distillery in Scotland. Remarkably balanced—smoky, sweet, and smooth. A good value at all ages, with the twelve-year-old and eighteen-year-old perhaps the best values, and the 1977 Bicentenary also very much worthwhile at about $150. I once had the great privilege of sampling a 1958 single single, and it remains my favorite whiskey ever ($1900 a bottle!).

4. Glenmorangie. Rhymes with “orangey.” A wonderful Highland malt that comes in a variety of excellent finishes—Portwood, Madeira, and sherry. I wasn’t crazy about the fino sherry finish, though Michael Jackson rates it an 89 out of 100. I’d like to try the Sauternes finish, which sounds wonderful. Best of all: the 1971, of which I’ve owned and finished two bottles. I’m now more than ready for a third.

5. Balvenie. A Highland malt that Michael Jackson aptly describes as “the most honeyish of malts.” I had my first (and second and third)—the twelve-year-old double wood—beside the fire in the Garden Bar at London’s Goring Hotel on an unusually chilly May evening, Robert Whiting’s Tokyo Underworld in hand, and the taste of the Balvenie always reminds me of the feel of that trip and that moment.

6. Laphroaig. Along with Lagavulin, Islay’s best-known malt. Laphroaig was the favorite of Trevanian’s assassin Jonathan Hemlock in The Eiger Sanction and The Loo Sanction, and of course it’s a favorite of John Rain as well. The fifteen-year-old is perhaps the best value, but the rare forty-year-old is certainly worth the $600 if you can spare it. Perhaps best of all is the sherry-finished thirty-year-old—an unusual but beautiful balance between sweet sherry and smoky peat.

7. Lagavulin. From a distillery next door to Laphoaig, another stunning Islay malt. Like most of its Islay cousins, Lagavulin is characterized by its smoky, peaty notes (peat is burned to dry the sprouted barley), by the salty tang the liquid picks up from the nearby sea air, and by a distinctive oiliness you can see on the glass. The Islay malts are sublime, but probably not for beginners and ultimately not for everyone. The sixteen-year-old offers one of the best values of all whiskeys.

8. Ardbeg. Another excellent Islay malt, especially delicious in its older bottlings. Try the Provenance, cut with a little water to bring out the flavor and soften its near 56 proof. I had my first Ardbeg in Osaka’s Bar Satoh, the best whiskey bar in the world, and the taste of Ardbeg always takes me back there.

9. Bowmore. Another Islay malt, but different from most: as Michael Jackson says, “The whiskies of Bowmore are between the intense malts of the south shore and the gentlest extremes of the north. Their character is not a compromise but an enigma�”. Best value: Bowmore Legend. Best taste: any of the over-twenty-five bottlings.

10. Springbank. From Campbeltown, traditionally made with local barley and dried over local peat, Springbank is known for its salty, oily character, balanced with sweetness in varieties finished in sherry casks. I’m not crazy about the widely available twelve-year-old, but the twenty-five-year-old is divine. With luck, one day I’ll get a chance to try the 1966.

Rain's Top Ten Jazz Albums You Might Not Have Heard Of

(or even if you have, they’re worth another listen)

Eric Alexander

Young tenor saxophonist with a ton of heart. Start with Nightlife in Tokyo, of course, nothing fancy, just terrific jazz.

Monica Borrfors

Swedish vocalist I first heard in Bar Satoh in Osaka, world’s best whiskey bar. Slowfox is a collection of songs in English, all rendered in Borrfor’s warm, slightly husky, beautiful voice.

Charles Brown

Brown’s voice contains pain and hope and the wisdom of experience, and his piano is top-notch.

Akiko Grace

Bill Evans, Thelonious Monk, Akiko Grace. Her piano is that good. Love and loss and hope and elegy—I don’t know how someone so young can understand and express it all, but Japanese composer/pianist Grace does.

Patricia Kaas

French vocalist with a wonderfully alluring voice, try Tour de Charme, which has two tracks in English, the rest in French.

Marisa Monte

Brazilian pop? Jazz? Choro? Who cares? Monte’s voice is so enchanting that it doesn’t matter if you can’t understand the Portuguese lyrics. Start with Rose & Charcoal.

Junko Onishi

Japanese pianist I first saw in Club Alfie in Tokyo, where she provided the inspiration for the character who became Midori Kawamura. Plays like an angry Thelonious Monk, as Alfie’s mama-san might put it,

Brenda Russell

Russell is hard to classify—jazz, light jazz, R&B, soul. Her voice is a caress—she can lull you to laugh, to sleep, to tears.

Luciana Souza

Is is jazz or choro? Who cares? Souza’s vocals are a delight. Listen to the voice and you’ll fall in love with the woman.

Toku

Japanese flugelhorn player and vocalist with an assured baritone voice. A terrific performer—at the Tokyo live houses, Toku packs ’em in.

Join the Fight

Join the good fight against the forces of evil! Stop saying “like” and “you know,” and ask other people to stop, too. With all the progress civilization has made against indoor public smoking, surely there’s hope in the fight against linguistic viruses, too?

Verbal tics tend to fall into three broad categories, but share a common cause and create a common impression: the speaker lacks confidence.

In the first category, we have the hedge words: like, you know, sort of, kind of, and basically. The hedge tics flee from precision and wallow in vagueness. It wasn’t milk, it was, you know, like, milk (does that mean it was cream? Butter? White paint?). It was sort of an attack on his character (but the attack failed? Got called off? What?). I basically agreed with him (but I also disagreed. So what am I saying? What’s my point?).

If you talk this way, it sounds as though you’re afraid to take a position, doubtful about the point you’re trying to make, or otherwise unsure of yourself. Is this how you want to be perceived?

Next we have the intensifiers: very, literally, truly, and really. On the surface, these have the opposite effect of the hedge words—after all, the speaker is insisting that whatever he’s saying is very, really, truly, literally the case. But these words tend to convey an impression of protesting too much, of fear that the speaker won’t be taken seriously if she doesn’t add that she really, really means this. The intensifiers feel like an email with subject line, “Please Read This! Please!” They’re like salt in the hands of a chef insecure about the taste of his cooking: they get overused to conceal a lack of other flavor. And some chefs are so insecure they even salt foods that shouldn’t take salt in the first place. “Very unique,” anyone? Very necessary?

Third are buzz words and cliches. These vary among industries and cultures, but the basis for their use is the same: “I’m not sure what I’m talking about, but if I use well-worn phrases and ones that seem to be in vogue right now, I’ll sound smarter.”

No, you won’t. Not unless your thoughts are original and insightful. If they’re not, hackneyed speech might fool a few people—but not anyone who was worth fooling in the first place.

I’ll keep adding to this page, but this feels like a good start for now. If you have a linguistic pet peeve, shoot me an email, and maybe it’ll make its way onto this page and help make the world a slightly better place.

Join the fight!

Sign up for Barry's Newsletter: Subscribe